[ad_1]

From the Spring 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Birding during migration means ample opportunities to rack up lifers; add to county, state, and patch lists; score the earliest or latest arrivals of species; and clock in record high counts.

There are endless methods for finding birds that come with years of experience and experimentation. I’ve used a few favorite techniques to help me find 185 species, including rarities like Painted Bunting and Connecticut Warbler, in Brooklyn Bridge Park—a narrow, 1.3-mile stretch of urban waterfront in New York City that attracts nearly 5 million human visitors each year.

By varying the way you scan for birds and strategize for birding, you’ll score lifers and rarities and gain a front-row seat to the spectacle of migration. Add in a little tech support from eBird and the Merlin Bird ID app, and you’ll take your birding enjoyment to a new level.

1. Systematically scan open areas and edges

Birds are great at hiding in plain sight. Anytime you come upon an open space like a field, lawn, beach, water body, or muddy area, do a systematic check. First, investigate all perches around the perimeter including treetops, snags, posts, and cables. Next, scan where the open space meets dense habitats such as reeds, shrubs, woodland, rocks, etc. This is a great way to find birds like bitterns and rails along marsh edges or sparrows and wrens edging out from meadow shrubs and scrubby beach dunes.

Now that you’ve covered the perimeter, carefully check the open area itself. Scan in an “S” pattern, moving left to right in a row, then right to left in the next row, and so on. As you do this, a field might come alive with a flock of Horned Larks, or your eyes might land on a Snowy Plover on the beach. I recall scanning the mudflats of a large Arizona wetland for at least 10 minutes before scoring a lifer; not one but three American Pipits were foraging in plain sight.

2. Eke birds out of the sky

Spring and autumn are great times to look high in the sky for migrating birds, whether they be hawks, kites, and eagles soaring at upper elevations, or large clouds of blackbirds in the distance. And the best part is that your binoculars will allow you to pick some of these migrants out of thin air.

Start by choosing a distant reference point, like a tree line, row of buildings, snag, or light post—even a moving object like a plane. Focus your binoculars on the object, then look beyond it for birds in flight. By using this distant-object focus-and-scan technique, raptors and flocks come in and out of view quickly. It’s a little bit like looking at stars in the night through binoculars; once you focus on one star, whole other constellations appear that weren’t visible to the naked eye. But in this case, you’ll discover birds that were flying unseen at high altitudes.

You might notice a teetering V-shape in the distance (Turkey Vulture), a soaring Broad-winged Hawk or Golden Eagle, or Sandhill Cranes flying in formation. Birds flying in the distance also make great reference objects themselves; I once spotted a Mississippi Kite soaring far behind a pair of Black Vultures I was observing from a Florida parking lot.

Certain times and weather conditions are better for finding high-flyers. When it’s windy, raptors are possible throughout the day; on warm windless days, the afternoon is more productive as raptors ride the rising thermal currents. Use the springtime’s southerly winds as a cue to look for migrating waterfowl that ride the air currents northward (and the same with northerly winds in autumn). Raptor and waterfowl migration starts in March and will be at its best through mid-April.

3. Take a seat

To migrating songbirds, we humans are ominous giants. No wonder they run and hide when we approach.

We appear much less threatening when seated, which can often result in birds—especially skulking, ground-dwelling species—that edge out from dense cover and into view. Next time you see a bird abscond into low and dense vegetation, take a seat nearby on a stone, bench, or even better, right on the ground. The bird will likely reappear within a few minutes to forage out in the open, along with others not visible before.

Ground-level birding is a great way to relocate unidentified birds along a trail or lawn edge, such as sparrows, wrens, and certain warblers that run into the brush or flit further into dense vegetation. Take a seat to wait for a bit, and species like Lincoln’s Sparrow, Marsh Wren, or your most sought-after skulker may reappear and give you great views.

Some birds may even start to approach you if you happen to be seated along the path of their foraging; I once had a Golden-crowned Kinglet hop onto my knee as it was feasting on gnats buzzing up from a park lawn in New York City.

4. Practice tracking birds in flight with common birds

Some of the most sought-after migratory birds are species that are constantly on the move, flitting and zipping in and out of view, like Blue-gray Gnatcatchers and Blackburnian Warblers. You can improve your chances of species ID at a glimpse by improving your skills at identifying birds in flight.

Fine-tune this skill by practicing on the common birds around you that you see all the time. I often use House Sparrows as my subjects; the smaller the better since the ultimate goal is to track warblers. Start by dialing in the focus on your binoculars to roughly the range where your birds will be, so you can quickly adjust focus when a bird comes into view. Then engage your peripheral vision to detect birds flying around you. When you see one, lock your eyes on it as you raise your binoculars, and keep your eyes on the bird until it lands or disappears out of sight.

With a little practice, you’ll be quickly and comfortably locking focus on birds in flight, and able to pinpoint where a bird lands to try to get a better look. Birds will also seem to slow down for you, making it easier to detect more of their identifying features. I find focusing on a bird’s head to be most helpful for IDing species on the wing. Note things like bill shape, the presence of an eyering or eye stripe, and contrasting throat color. Once the face becomes easy to ascertain in flight, look for other identifying traits like tail length and flight style.

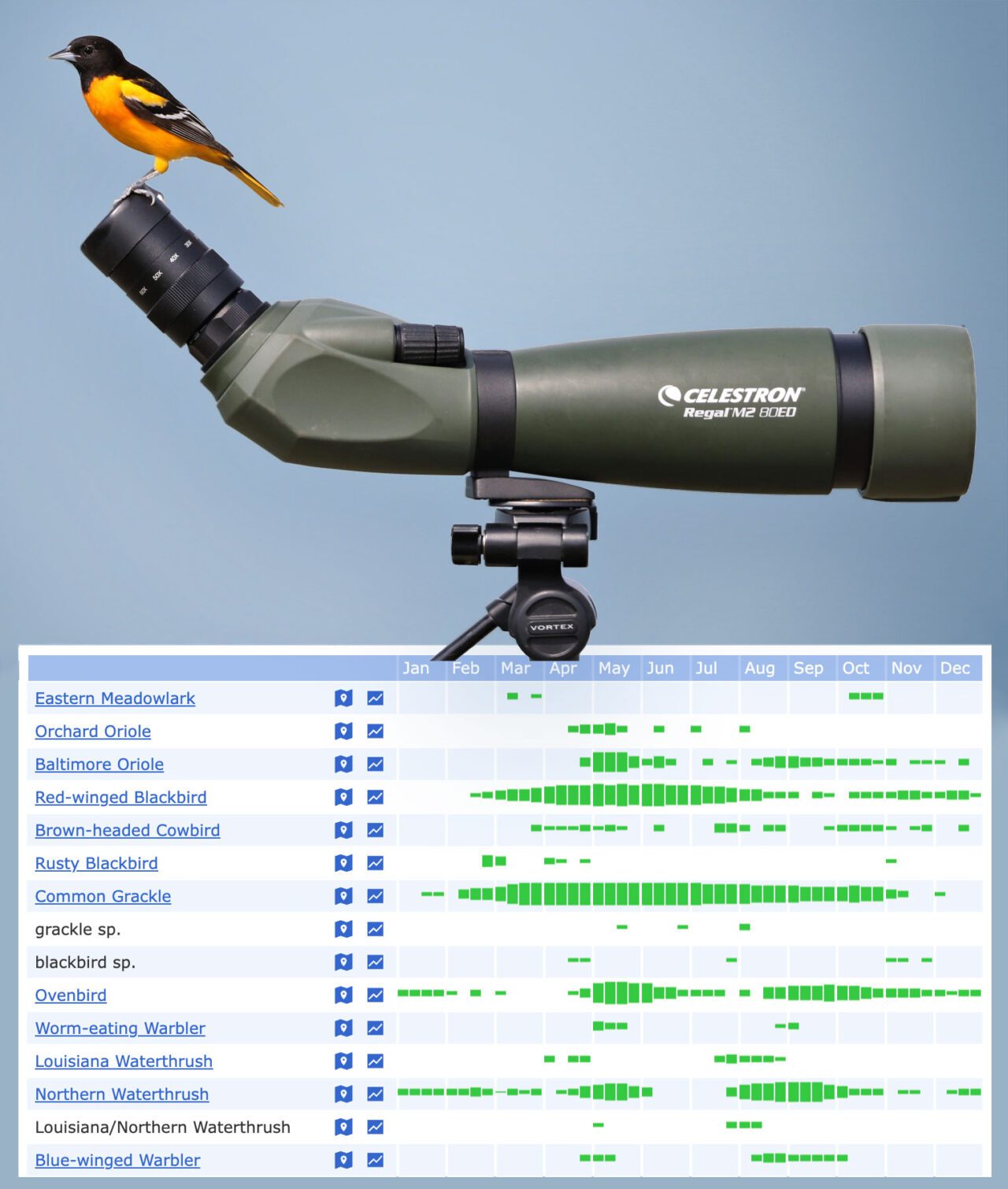

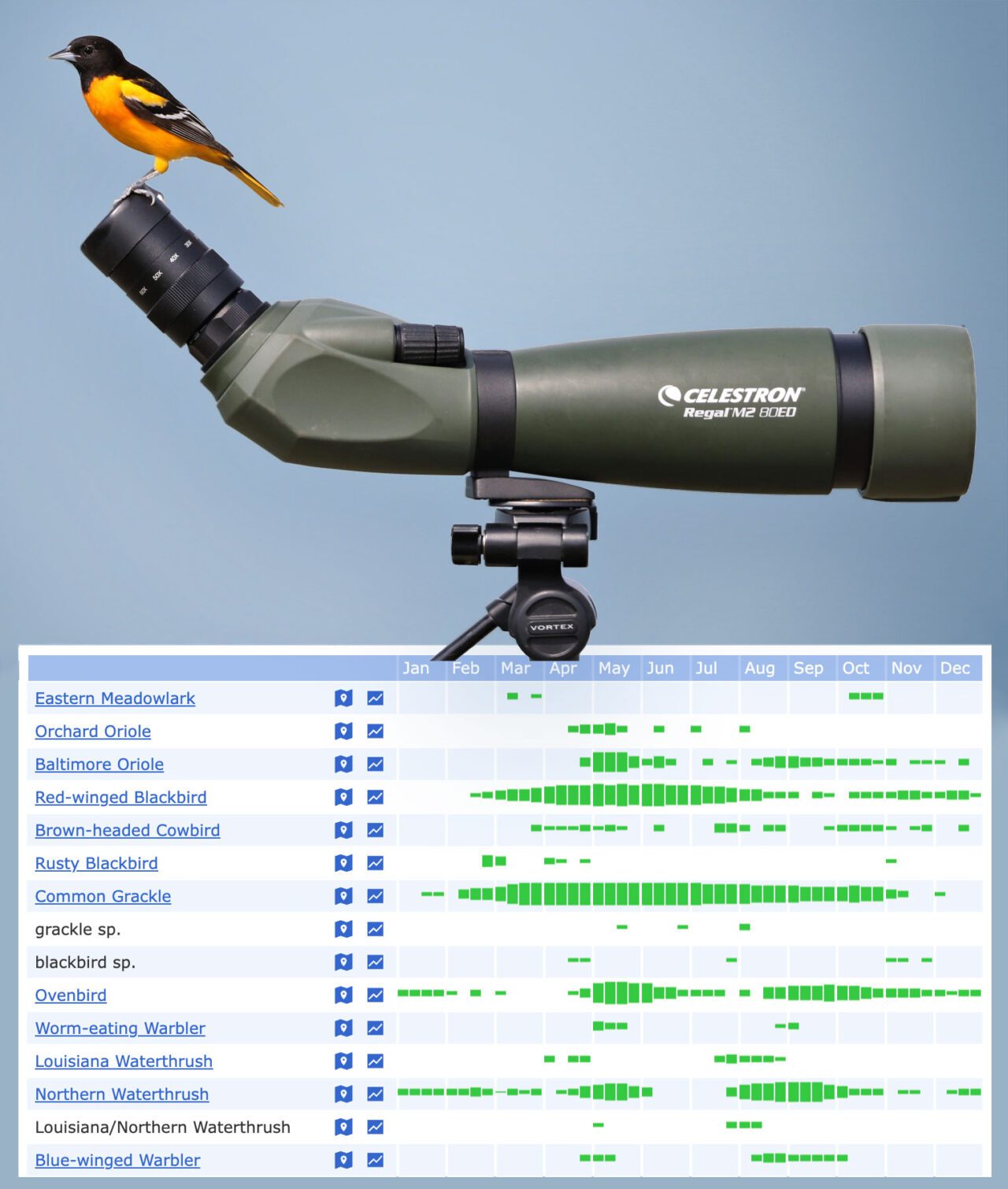

5. Scan eBird bar charts to see who might be in the neighborhood

One of the best ways to find more birds is to know what to expect and where. eBird’s weekly bar charts are my favorite resource during migration to see which species are likely to be in town and which ones might be coming next.

Visit eBird Explore and enter your county, then select Bar Charts (or “Region navigation” on your phone screen to expand the menu options). At a glance, you’ll see which species are expected to arrive first during migration, such as blackbirds, and how long they can be expected to stay. You’ll notice peaks in many birds’ frequency during migration months, and which weeks offer the best chances to add them to your list.

For those who want to break a record in their local birding scene, eBird bar charts are a great way to try for the earliest or latest record of a species in an area. Note the week before or after the relevant data block and spend more time and effort in a bird’s habitat during those weeks. Bar charts also illuminate opportunities for species high counts; look for chart peaks of flocking species such as blackbirds to know the best times to scan the sky.

6. Target the birds you need

If you’re looking to add more birds to your life, state, or county list, focus your efforts on the species you’re missing with eBird Targets. Just go to the site, enter your area of interest, adjust the “Time of year,” and click “Show target species.” A list of species you need for a selected region appears along with their frequency percentages; you can search targets for your county, state, country, or world life list.

7. Let Merlin listen for you

The Merlin Bird ID app’s Sound ID feature listens for birds and shows species identification suggestions for the sounds it detects. It often picks up sounds that people don’t notice, such as distant birdsong or calls obscured by ambient noise. It also easily detects the high-pitched sounds of birds like Blackpoll Warblers and Cedar Waxwings that might be too high for some people to hear. I often let Merlin listen to canvass the sounds of an area, especially in spring and summer. If it suggests a rarity or bird I’m hoping to add to a list, I know to focus my efforts on that species’ preferred habitat.

8. Always be birding

One tried-and-true method of seeing more birds is to expand your definition of birding. Heading to the grocery store? Take a quick minute to investigate that tiny bird atop a tree in the store’s exterior landscaping. Taking the kids to the playground? Steal a few seconds to scan shrubs beyond the swing set for sparrows and warblers. Going to a baseball game at night? In between innings, scan the area in front of the floodlights to see if any nightjars are out hawking insects.

Treat every outing as a bird-finding opportunity. Pack your binoculars or keep a spare set in your car, purse, or backpack so you don’t miss a bird. Always be tuned in to movement and sounds, as well as potential perches and other surrounding habitats.

Even the smallest patches of suitable habitat can attract birds everyone wants to find. One spring, I went to my brother’s place in Brooklyn to have dinner on the terrace and packed my binoculars just in case. As the sun started to set, I noticed movement on a nearby rooftop in a planter holding a 2-foot pine. When I looked through the lenses, I couldn’t believe what I had found: a migrating Pine Warbler in a tiny pine tree!

There are likely pockets of bird habitat everywhere in your day-to-day comings and goings—store and office parking lots, for example, are often bordered by mini marshes, wetlands, or woodlands. Take it from me, if there’s one thing I’ve learned as I approach the 200-species mark in my birding patch beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, it’s that more species await in the most unlikely places. There is always another bird to find.

About the Author

Heather Wolf is the author of Find More Birds and Birding at the Bridge. A Brooklyn-based birder, photographer, and educator, she works with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology as a web developer, teaches birding classes at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and gives walks and talks for various organizations in New York City and beyond.

In her new book, Find More Birds: 111 Surprising Ways to Spot Birds Wherever You Are (The Experiment, 2023), Heather Wolf shares her very best tactics for sharpening a birder’s senses and becoming more aware of the birds that are out and about every day. Learn more and buy the book.

[ad_2]